Hebraicizing Oedipus

By Kalman J. Kaplan

As a professor, a practicing clinician and as a Jew, I have long pondered the question of why Freud, a fellow Jew, was so enamored by ancient Greek narratives rather than biblical ones, specifically the story of Oedipus. Even more, I have become convinced that Freud to some degree hijacked this legend for his own purposes. It seems to me that the legend of Oedipus is not primarily about what Freud calls the “Oedipus Complex”, but the far deeper question of whether one can escape one’s fate, or whether one is imprisoned is by the impersonal forces of moira (fate) and ananke (necessity). The great Russian Jewish philosopher, Lev Shestov, has written of this in his monumental work “”Athens and Jerusalem.” Indeed, I have written or co-written a number of books on this issue, the latest being “Biblical Psychotherapy: Reclaiming Scriptural Narratives for Positive Psychology and Suicide Prevention,” several of which have been reviewed by the late Reuven Solomon in The Jerusalem Report.

More recently, I have turned to writing plays and have published a trilogy on the story of Oedipus from a biblical perspective. The theme of my work is that Oedipus was entrapped by a misleading response from the Oracle of Delphi (the Pythia). After hearing a drunken man at a dinner party in Corinth question his lineage, Oedipus travels to Delphi, and asks her whether the “parents” who raised him (King Polybus and Queen Merope of Corinth) were indeed his natural parents. Rather than answering his question, the Pythia simply tells him that he is fated to kill his father and marry his mother.

Thinking this prophecy referred to Polybus and Merope, Oedipus flees Corinth to avoid fulfilling this prophecy. Oedipus unfortunately flees to Thebes, where unbeknownst to him, his birth parents (King Laius and Queen Jocasta) reign. Along the way, Oedipus kills an older man on a crossing “where three roads meet” over a dispute over right of way-an older man strikes Oedipus over the head with a spiked club. A fight breaks out and Oedipus kills this man. Who unbeknownst to Oedipus, is Laius, his natural father. Continuing to Thebes, he overcomes a Sphinx, a monster with the head of a woman, the body of a lion and the wings of a bird, who devours passers-bye who cannot answer her riddle(s). Oedipus subdues the Sphinx by answering her riddle(s) correctly and is rewarded by being named King of Thebes and is married to the widowed Jocasta, who he does not realize is his natural mother. Together, they have four children. A great plague falls upon the city which Oedipus is told is due to the murderer of Laius residing in the city. Oedipus decrees that the murderer should be found and banished from Thebes, not realizing he is the one who has killed Laius, albeit in self-defense. When Oedipus discovers this, his mother hangs herself and he takes out his eyes.

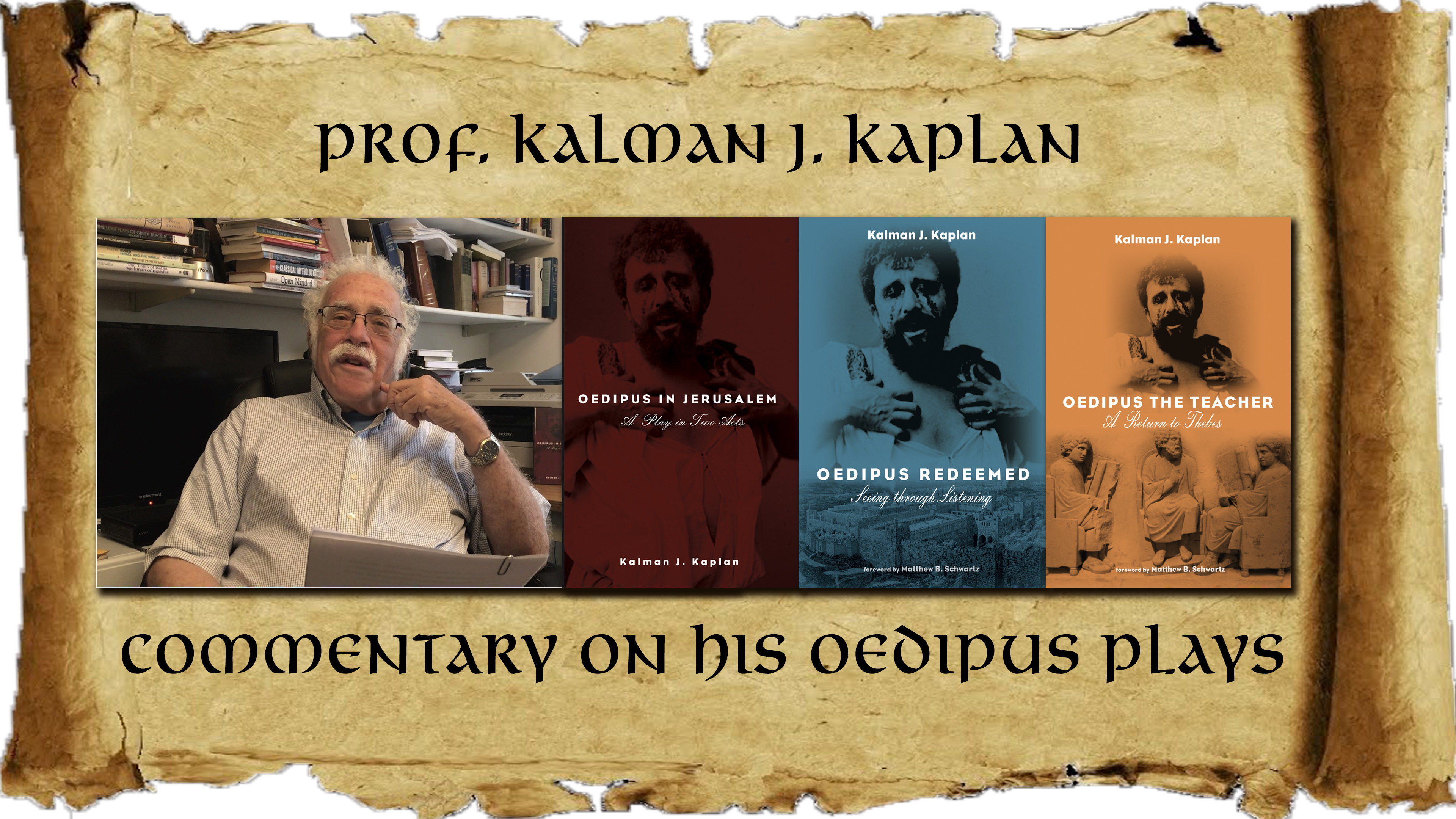

I have become convinced that Oedipus was entrapped by the Pythia and was absolutely innocent of intentionally killing his father and marrying his mother, when, by fleeing from Corinth, he was trying to avoid doing this. This has led me to write a modern trilogy of three Oedipus plays (‘roll over Sophocles”, to paraphrase the rock musician Chuck Berry): attempting to view Oedipus through biblical-Jewish lenses. Oedipus in Jerusalem, Oedipus Redeemed: Seeing through Listening and Oedipus the Teacher: A Return to Thebes. The first two have already had public readings and have been videotaped. Let me summarize the entire trilogy below. Let me admit that I have taken liberties in the name of poetic license with the historical period these figures found themselves in.

Oedipus in Jerusalem: A Play in Two Acts

In the initial play in my trilogy, Oedipus in Jerusalem, I relate the narrative of Nathan, the biblical prophet, encountering the blinded Oedipus wandering alone outside of Thebes. After hearing his story, Nathan becomes convinced that Oedipus is innocent of intentionally killing his father and marrying his mother and was in fact trying to avoid committing these acts but was entrapped by misleading answers by the Oracle of Delphi. Oedipus insists he is the “worst of the worst” but against his protestations, Nathan brings Oedipus to Jerusalem to be tried at the Jewish Sanhedrin. The Greek playwright Sophocles serves as the prosecutor, and Nathan acts as the defense attorney for the blinded Oedipus who insists he is guilty.

The council of sages of the Sanhedrin acquit Oedipus on both charges because it concludes he is done in by “fate,” (the Greek moira) which actually is not something impersonal and unchangeable at all. Rather Oedipus’s actions are judged to be the result of incomplete information, misleading riddles, and confusing statements, leaving him without accurate knowledge of his situation, and thus entrapping him in performing the very actions he is trying to avoid.

A strong cross-examination emerges at this point by Nathan of the Oracle of Delphi, illustrating this point, Greek thinking is indicted as representing an abstract geometrical concoction rather than any organic morality inherent in Biblical thinking. Oedipus is reprimanded for only one action, taking out his eyes, which is expressly forbidden in the Hebrew Bible and Jewish law as prohibited self-mutilation. As Oedipus has not been formally accused of this act by the Greek Sophocles or Teiresias, no punishment can be levied, though the Sanhedrin comments on the act as being repulsive and forbidden by Jewish law.

Oedipus, however, thoroughly indoctrinated in Greek thinking, emotionally refuses to accept the verdict of innocent, shouting that he is the “worst of the worst,” guilty of the polluting acts of patricide and incest with his mother.

Oedipus Redeemed: Seeing through Listening

This second play, Oedipus Redeemed, begins at this point, and focuses on Nathan and Sophocles, combining forces to try to help Oedipus accept his acquittal. First, they present Oedipus with two dialogues of historical/biblical characters within the play.

The first dialogue is between the Greek chronicler Diogenes Laertius and the biblical Job. Laertius describes the suicide of Zeno the Stoic – he holds his breath until he dies in response to the minor mishap of wrenching his toe. Job, in contrast, continues to affirm life despite the monumental losses he has experienced. When Job asks Oedipus whether he, like Zeno, sees what happened to him as a sign that he should kill himself, Oedipus is noncommittal, saying that “Zeno sees it this way.” When Oedipus is asked why he did not kill himself, despite feeling so guilty, he responds that he did not want to see his parents in Acheron (the other world) after what he had done. This provides an opening designed to uncover the possibility that Oedipus was not suicidal, after all, he did not commit suicide after he blinded himself even though he now would not see his natural parents in the next world.

Nathan and Sophocles focus on the secondary psychological benefit Oedipus has received from insisting on his guilt, and on his coming to terms with the fact that he had blinded himself needlessly if he was innocent. And this leads to the second dialogue presented between the biblical prophetess Deborah and the blind Greek seer Teiresias which focuses on the biblical story of Samson being betrayed by “following his eyes.” Insight is contrasted with sight.

Oedipus’s only surviving child, his daughter Ismene, reunites with Oedipus, telling him she loves and needs him. The play ends with Oedipus’s return to the Sanhedrin, tentatively and tearfully accepting his acquittal.

Oedipus The Teacher: A Return to Thebes

Oedipus Redeemed ends with the Greek Oedipus returning to the Jewish Sanhedrin in Jerusalem where he agrees to try to accept emotionally the acquittal he has received with regard to intentionally killing his father and marring his mother, something he had rejected at the end of the first play of this trilogy, Oedipus in Jerusalem. In this third play of this cycle, Oedipus the Teacher, Oedipus returns to Thebes with Nathan and Sophocles where Oedipus does come to accept his acquittal and where with the help of his daughter Ismene and his assistant Kallias, he attempts to teach Theban children the biblical lessons he has learned regarding free will as opposed to fatalism (the Greek “moira”).

This is complicated by Kallias and Ismene falling in love with each other and Kallias developing resentful feelings towards Oedipus himself, whom he sees as psychologically “castrating him” and blocking him in his own development. Sophocles invites the Greek Hesiod to discuss the story in his Theogony of Cronus cutting off his father’s genitals. The prophetess and judge Deborah enters the scene and with the help of Nathan discusses the contrasting biblical story of him of Abraham circumcising his son Isaac (as an alternative to castration).. The play ends with Oedipus endorsing circumcision as a neutralizing of the castration desire of the father towards his son, and as a way of neutralizing and transforming this fear on the part of the father towards the son. Rather, as Oedipus now insists, the father has nothing to fear from his son, and indeed wants his son to surpass him, each generation serves as a link in the chain to the next.

Oedipus gives his blessing for Ismene to marry his Theban student Kallias , and he, like the biblical Naomi is welcomed into their home as a doting grandfather. The play ends with the announcement that Oedipus’s course has been chosen to be taught throughout Greed, Oedipus exclaims that he is finally happy. I think the time is long overdue to embrace a biblical theater, psychology, and psychotherapy, all embracing the sanctity and the innate purposiveness of life rather than an often-destructive search for meaning.

Some Concluding Observations

We have undertaken the task of developing public readings of these plays at the Greenhouse Theater in Chicago. The readings of the first two plays (Oedipus in Jerusalem, and Oedipus Redeemed) have been completed. The reading of the third play (Oedipus the Teacher) is waiting for the devastating plague we have been experiencing to abate. During the reading of the first two plays, I experienced something quite interesting. Our cast came from all over the political map, some on the left and others on the right, and some apolitical. The majority of our cast was Jewish, but not all, and included several evangelical Christians. Our cast included literature professors, attorneys, psychiatrists, psychologists, former tour guides in Israel, Jewish activists, and even a former nun. Some were American, others were European, others Israeli. What emerged, to me, strikingly was the observation that these plays clarified to our readers that the struggle of our age not been between left and right per se, but really what is has always been, between Israel and Hellas. This is what these plays are about.

Kalman J. Kaplan, Ph.D. is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry,

University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine